News Story

Sensor Advancement Breaks Barriers in Brain-Behavior Research

The publication's first authors, Overton and Balamurugan, prepare one of the samples used in the research.

New, interdisciplinary research from the University of Maryland (UMD) A. James Clark School of Engineering and the UMD College of Behavioral and Social Sciences is opening the door to better understanding the relationship between neurohormones and behaviors. The team proved that a newly improved electrochemical sensor can reliably measure serotonin levels in crayfish blood and found that serotonin levels changed when the animals experienced different social situations. A paper detailing the study, “Electrochemical sensing of hormonal serotonin levels in crayfish,” is now available online and will be published in March 2026 in the journal “Biosensors and Bioelectronics: X.” It was written by Sydney N. Overton (ECE, ISR, Fischell Institute, MATRIX Lab), Kanishka Balamurugan (PSYC, NACS), Jens Herberholz (PSYC, NACS), and Reza Ghodssi (ECE, ISR, Fischell Institute, MATRIX Lab).

“This impressive breakthrough in sensor development will lead to major advancements in brain-behavior studies and highlight the significant discoveries that can be realized when engineering and behavioral sciences experts work together,” said Dr. Ghodssi, UMD Distinguished University Professor and MATRIX Lab Executive Director of Research and Innovation. “We thank Biosensors and Bioelectronics: X for recognizing this great milestone in our research.”

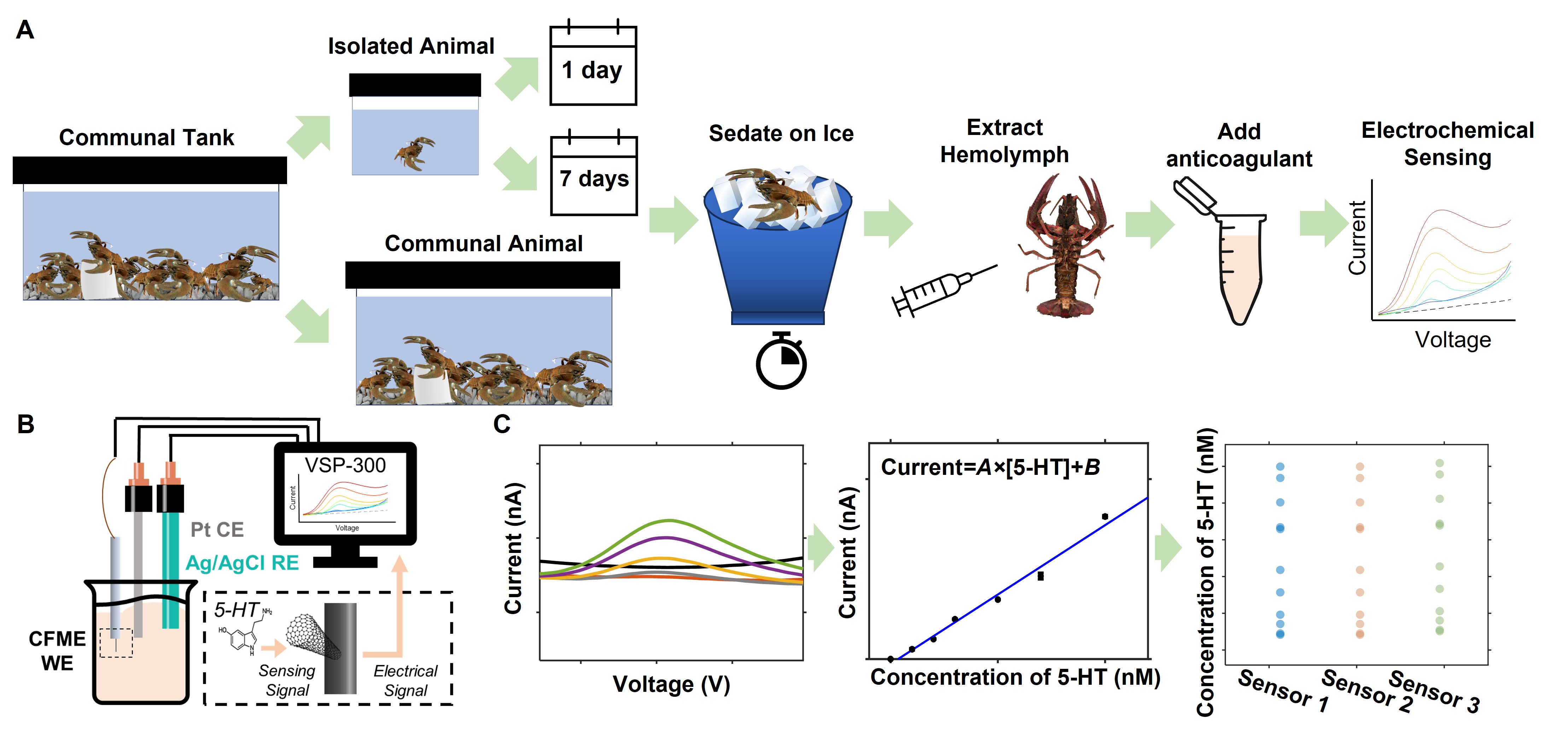

Serotonin affects behavior and mood. In crayfish, levels directly affect conditions like anxiety and behaviors like aggression and social dominance. The crustacean species make a great subject for hormone-behavior studies because they have a reduced nervous system, identified serotonin-producing neurons, and known links between serotonin levels and behavior. However, it is extremely difficult to measure serotonin in them because their concentrations of the neurotransmitter are low and many other chemicals interfere with detection. Previous electrochemical sensors could not reliably measure naturally occurring levels of serotonin and often required injecting serotonin to get a readable signal.

To address these barriers, the UMD research team improved their device by changing how they treated the surface of the sensor. The team coated its sensing element in small carbon nanotubes, improving its sensitivity, and Nafion, a thin, flexible, polymer coating that selectively diffuses serotonin, and used electrochemical etching to improve signal quality. This drastically improved the signal-to-noise ratio, meaning the measurements stood out more clearly from background interference. That led to reliable detection and accurate measurement, without the need to inject external serotonin.

With this improved sensor, the team was able to determine that social isolation does change serotonin levels, with different effects depending on the species and length of isolation. Patterns reflected different natural social lives and various stress adaptation strategies. This demonstrates that social environments can rapidly alter hormone levels. Though isolation effects differ between species, researchers found some universal truths: Social isolation is linked to changes in hormonal chemistry, with crucial neuromodulators like serotonin responding to experiences.

With this improved sensor, the team was able to determine that social isolation does change serotonin levels, with different effects depending on the species and length of isolation. Patterns reflected different natural social lives and various stress adaptation strategies. This demonstrates that social environments can rapidly alter hormone levels. Though isolation effects differ between species, researchers found some universal truths: Social isolation is linked to changes in hormonal chemistry, with crucial neuromodulators like serotonin responding to experiences.

“Our collaborative work is a significant step towards understanding the relationship between monoamine fluctuations and neurobehavioral outcomes,” said Dr. Herberholz, a UMD Department of Psychology Professor and a coauthor on this paper. “Traditionally, it has been difficult to obtain such direct measurements, and the work’s promise lies in its suitability for future in vivo real-time detection of rapid changes in hormones during the expression of natural behaviors. For example, uncovering the neurochemical dynamics during social dominance formation or stress adaptation under changing social conditions has great potential to inform studies across a variety of organisms, including those of biomedical importance.”

The study demonstrates that the improved electrochemical sensor can be used to answer real biological questions related to how hormones change over time and how neurochemistry and behavior are connected. It also sets researchers up for future success in studies related to mental health, stress, and social behavior. In the future, the sensor could be integrated into a wearable system. This would allow for real-time serotonin monitoring, a big step toward understanding how hormones fluctuate during behavior and how outside forces alter neurochemistry.

Published January 13, 2026